# Lacrimal System and KCS

How Tears Affect Vision

Tears (not the cornea) are also technically the first optical surface met by light entering the eye. The light travels through the air first and then hits the tear film and refracts (bends) at the air-liquid interface. The light then travels from tear film to cornea which have similar indexes of refraction (going from a liquid-to-pretty-liquidy medium in contrast to air-liquid). In fact people with dry eye may not have obvious signs of discomfort or feelings of dryness initially, but may instead notice blurry vision that is not associated with near or far sightedness. This is due to the lack or alteration in the tear film.

If you are studying for NAVLE however, the answer to the question about what causes the most refraction in the eye is going to be the cornea (usually tear film is not even an option) because that is the starkest change in light refraction with the light going from air to tissue. Light going traveling through cornea to aqueous to lens to vitreous is only minimally changed because the medium the light passes through is largely the same (water). The lens only bends the light just enough so that it reaches the retina appropriately.

In fish, where there is no air-tearfilm interface, the lens does most of the heavy-lifting with respect to refraction. There the lens occupies a much larger volume because it really has to be bend the light significantly so that it lands on the retina appropriately. Optics is neat!

# Three components of the tear film

Understanding of the tear film and how it is structured continues to evolve but essentially the there are three main components of the tear film originating from 3-4 different tissues

- Aqueous – comes from the lacrimal gland (66%) and gland of the third eyelid (33%). Makes up the majority of tear film. Maintains an optically uniform corneal surface, helps remove foreign matter from the corneal surface, aids in lubrication, and provides nutrients to the avascular cornea.

- Mucous/Mucin - comes from goblet cells of the conjunctiva mostly at the fornix - helps the aqueous part of the tears adhere to the cornea and acts as a surfactant to help them spread across the cornea, traps bacteria and particulate matter.

- Lipids - comes from the meibomian glands in the eyelid margin - prevents evaporation of the aqueous layer and spillage of the tears over the eyelid margin.

# Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS)

A deficiency in tear production of the severity that the health of the eye is compromised. Most often is a result of a deficiency of the aqueous layer.

# Clinical Signs

- Hyperemic conjunctiva - can be the earliest sign noted

- Mucopurulent discharge - secondary to bacterial infection and the mucous builds up

- Keratitis - pigment, corneal vascularization, keratinization, ulceration, perforation

- Dull appearing cornea sometimes with severe blepharospasm

- Squinting, rubbing at the eyes

# Diagnosis

- Clinical signs (see above)

- Schirmer Tear Test

- Normal: 15-25mm/min

- “Gray Zone”: 10-14 mm/min

- Subnormal: 0-10 mm/min

- If the tear production is in the gray zone then go by the clinical signs or recheck in a couple of weeks.

- Qualitative tear film deficiency can cause signs similar to qualitative tear film deficiency but occurs when there is either too little lipid or mucous (see more below)

# Differential Etiologies

- Immune-mediated (autoimmune adenitis) - most common cause of KCS in dogs

- Diagnosis

- Breed predisposition (Westies, Cockers, Bulldogs, Lhasa Apso and many others)

- No other cause found.

- Diagnosis

- Canine Distemper Virus and Feline Herpes Virus

- Toxic - sulfa drugs, etogesic (most cases have permanent KCS)

- Topical - atropine - temporary

- General anesthesia – temporary, but can last longer than 24 hours

- Neurogenic - facial nerve palsy, trigeminal nerve palsy

- Iatrogenic - removal of the nictitans gland. It used to be standard practice to remove the gland of the nictitans when a dog developed prolapsed gland of the nictitans (cherry eye). Now the gland is replaced.

- Chronic conjunctivitis - inflammation and scarring

- Lacrimal gland agenesis – rare but usually unilateral in very small breeds

- Radiation therapy – when the eye is in the field.

- Hypothyroidism may be associated with KCS

TIP

Ultimately the most common cause is immune mediated. The other causes can be mostly gleaned from comorbidities (dying puppy with ocular discharge - probably distemper) or common sense things (was the animal just under anesthesia or is on a lot of topical atropine?). Since hypothyroidism is a legit cause, a reasonble diagnostic to perform is a T4/TSH in a dog with KCS and concurrent signs of possible hypothyroidism.

# Treatment

# Medical

The first goal of medical management is to re-establish normal tear production. The earlier this is done (i.e. when the tear production hasn’t sunk too low) the better. In immune mediated cases (the majority) it’s important to start lacrimomimetics/tear stimulants early before immune-mediated destruction of the gland reduces the overall capacity for production. See below for discussion on what and how.

# Tear Stimulants

Cyclosporine - the “original” tear stimulant. Mode of action is complex - essentially blocks formation of interleukin-2 which reduces T-helper cell activation. How this actually translate to stimulated tear production is actually not fully known (yet).

Cyclosporine comes in a variety of strenghts and flavors. See below for more details:

Optimmune 0.2% - The “OG” cyclosporine. The only “commercial” product with a tradename (Optimmune). Is a 0.2% strength based in petrolatum oil/ointment. Any other concentration of cyclosporine or formulation will need to be obtained from a compounding pharmacy.

Cyclosporine 1-2% - to increase the strength/concentration of the cyclosporine you can get it reformulated as high as 2% (10x the amount as Optimmune). Is more better? Yeah probably. The author will go to 1-2% cyclosporine if the STT is moderate to severe (e.g. STT < 10 mm/min). Classically, 1-2% cyclosporine will be compounded in an oil of which there are many flavors - corn, coconut, MCT. Ultimately the vehicle is often inconsequential but oil-based suspensions may be irritating. Owners will report sudden squinting and redness shortly after applying. The author will usually warn people this may occur and consider switching to a more aqueous-based solution as that may be better tolerated.

Tacrolimus - the “newer” alternative to cyclosporine. Mechanism of action is similar to the cyclosporine but the target molecules are technically different. Still results in IL-2 decreases which interferes with cell mediated immunity. Can be found in many different formulations although the author will err toward the 0.03% aqueous suspension because the oils can get messy. Again - obtained through compounding pharmacies.

TIP

A study of cyclosporine vs tacrolimus showed that neither was consistently superior in terms of efficacy to the other but that one would occassionally work better than the other idiosyncratically. [1]

- Pimecrolimus - the newest kid on the block. Precious few studies on efficacy in comparison to other sister drugs (like cyclosporine or tacrolimus). Probably a drug of last resort if response to cyclosporine or tacrolimus is not enough.

# Tear Replacements

Tear replacements will never be enough to replace the real thing. They can serve as adjunctive treatments however and maybe can provide some momentary relief (stress on momentary).

Artificial tears usually comes in 3 main flavors - drops, gels, and ointments.

| Artificial Tear Type | Properties | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Drops | A plethora of products to be found over the counter, usually comes in either single-use preservative free forms or in multi-dose bottles. Not great as an artificial tear in veterinary medicine as the lubrication is only there for a brief period (minutes at most). People can dispense as needed into their own eyes but not so much in our patients. |

|

| Gels | Generally less messy than ointments but last a teensy bit longer than drops. Usually the author’s preferred tear supplement because it’s easier to apply and isn’t oily. |

|

| Ointments | The thickest artificial tear - usually contains some kind of oil-based medium (i.e. petrolatum). Theoretically lasts longer than any of the other tear supplements so probably best for severe cases. However, can get “messy” with chronically oily fur. Also harder to get out in a controlled manner for most clients - just need a tiny bit but usually more comes out. |

|

# Antibiotics/Anti-inflammatories

Tears normally contain some amount of anti-microbial substances (e.g. complement, antibodies, among other things). The deficiency of tears results in deficiency in these compounds which results in increased bacterial growth. The bacterial overgrowth (not quite an “infection” per se) can lead to increased buildup of mucous or color changes (e.g. green mucous). Additionally the dryness will lead to inflammation of the conjunctiva and cornea - the keratoconjunctivitis part of KCS.

Ideally we would like to counter the bacterial changes and inflammation by increasing tear production but you can also prescribe medications to directly counter these effects, if severe and warranted. Used solely though, they will not improve tear production and therefore effects are limited to when the drug is applied and all the while the lacrimal is scarring up with inflammation…

With regards to what kind of anti-inflammatory should be used, usually topical NSAIDs do very little to help and weaker steroids (like hydrocortisone) are likewise not terribly helpful. The author will occassionally resort to NeoPolyDex (ointment or solution) usually BID, as a means of helping with the secondary baterial overgrowth and keratoconjunctivitis at a BID dosing. However, it’s important to note that used in acute cases of KCS, there’s a risk of ulceration followed by stromal loss (e.g. melting or otherwise). Chronic cases with a lot of neovascularization, pigmentation, etc. are less likely to ulcerate and so NPD may be more comfortably used to help with discharge or discomfort.

# Medical Treatment Examples

Sometimes with all the possible treatment options, it’s difficult to know what to do. See below for some example treatment protocols that the author has used for varying situations of KCS with or without corneal ulcerations.

# Example 1 - acute, mild KCS, nonulcerative

5 yo English Bulldog presenting for pink eyes OU of 2+ weeks duration

Pertinent ophthalmic exam findings:

- Moderate conjunctival hyperemia

- Early superficial corneal neovascularization

- STT 10 mm/min OU

Example treatment plan for Example 1

Rx: Optimmune (0.2% cyclosporine) ophthalmic ointment OU BID FOREVER

Recheck: 1 month (can take a few weeks to kick in)

Comments: The corneal neovascularization is suggestive of a more chronic and meaningful problem (e.g. vs exposure conjunctivitis). In mild cases, can just try optimmune at the usual (BID) dosing. Cyclosporine and similar products can take up to 3 months to kick in but most cases will respond after a month.

In a bulldog which is a breed known for KCS (among the plethora of other ophthalmic problems) would continue the optimmune forever. Document improvement and continue rechecks of STT 1-2 times per year long-term. Can drop down to q24h dosing if STT > 15 mm/min or if epiphora is noted.

# Example 2 - subacute, moderate KCS, nonulcerative

5 yo West Highland Terrier presenting for mucoid discharge OU of 2+ weeks duration

Pertinent ophthalmic exam findings:

- Severe conjunctival hyperemia OU

- Significant superficial corneal neovascularization OU

- Thick mucoid discharge OU

- STT 6 mm/min OU

Example treatment plan for Example 2

Rx:

- Cyclosporine 2% (compounded) or Tacrolimus 0.03% OU BID-TID FOREVER

- Artificial tears gel/ointment of some kind OU QID

Recheck: 1 month (can take a few weeks to kick in)

Comments: The very low STT and significant corneal neovascularization is enough proof that KCS is in full swing. In severe cases (STT << 10 mm/min), would recommend using the higher concentration cyclosporine (e.g. 1-2%) or tacrolimus on a slightly more aggressive treatment frequency (BID-TID). Both these medications have to be compounded so will typically need to be ordered from a compounding pharmacy unless you stock it.

In a Westie which is yet another a breed known for KCS, would continue medications forever. If STT goes to normal, then can discontinue artificial tears perhaps. Document improvement and continue rechecks of STT 1-2 times per year long-term. Can drop dosing if STT > 15 mm/min or if epiphora is noted but usually not terribly likely if STT starts out very low.

# Example 3 - chronic, severe KCS, nonulcerative

5 yo Cocker Spaniel mucoid discharge OU of 2+ months duration

Pertinent ophthalmic exam findings:

- Severe conjunctival hyperemia OU

- Severe thick mucoid discharge OU - had to flush for 5 minutes to clear it out to see the eyes

- Marked corneal neovascularization & pigmentation such that interior of eye can’t be visualized OU

- STT 0 mm/min OU

Example treatment plan for Example 3

Rx:

- Cyclosporine 2% (compounded) or Tacrolimus 0.03% OU BID-TID FOREVER

- Artificial tears gel/ointment of some kind OU QID

- NeoPolyDex ointment/drop OU QID

Recheck: 1 month (can take a few weeks to kick in)

Comments: The very low STT and significant corneal neovascularization is enough proof that KCS is in full swing. In severe cases (STT << 10 mm/min), would recommend using the higher concentration cyclosporine (e.g. 1-2%) or tacrolimus on a slightly more aggressive treatment frequency (BID-TID). Both these medications have to be compounded so will typically need to be ordered from a compounding pharmacy unless you stock it.

In a Cocker Spaniel, which is yet another breed known for KCS (see a pattern here?), would continue medications forever. If STT goes to normal, then can discontinue artificial tears perhaps. Document improvement and continue rechecks of STT 1-2 times per year long-term. Can drop dosing if STT > 15 mm/min or if epiphora is noted but usually not terribly likely if STT starts out very low.

Compared to Example 2, this case is probably ok to use NeoPolyDex to help with the keratoconjunctivitis because the cornea is basically like “shoe leather” - so keratinized it’s highly unlikely it’ll ulcerate or melt on the steroids. The antibiotics could help reduce the bacterial overload too. It might have been ok to use in Case #2 too but depends on the chronicity (more chronic, more the cornea can adapt, the safer the steroids may be).

It should be noted that really BAD dry eye (STT = 0 mm/min), the lacrimal gland may never recover. Histologically these glands atrophy with the lacrimal adenitis and may never squeeze out a drop of tears ever again - treat KCS early! Still, treatment is warranted if only to try to help comfort and maintain vision.

# Example 4 - acute, severe, ULCERATIVE KCS

5 yo Shih Tzu redness, discharge, blepharospasm OD of 1 week duration

Pertinent ophthalmic exam findings:

- Severe conjunctival hyperemia OD

- Severe thick mucoid discharge OD

- Axial descemetocele or deep deep stromal ulcer OD!!

- No corneal neovascularization noted

- STT 0 mm/min OD, 10 mm/min OS Yes, it’s still possible to take a STT in an eye with a descemetocele if the dog is well-behaved

Example treatment plan for Example 4

Rx: Technically the first thing that should be done in a GP setting is to offer referral to an ophthalmologist to patch the descemetocele but if the owners want to take their chances (and since this is a medical example…) then the author would likely recommend the following:

- CONE AT ALL TIMES

- Serum/Plasma OS q1-2h

- Ofloxacin OS q2-6h

- Cyclosporine 2% (compounded) or Tacrolimus 0.03% OD BID-TID FOREVER

- Artificial tears OS q1-2h

Recheck: a few days to 1 week later

Comments: This dog is in rough shape - severe KCS with a descemetocele is generally not a winning combination. Perforation is a big risk. Dealing with these situations is really a waiting game for neovascularization to reach the descemetocele. Treatment goals are to prevent performation (the cone), prevent further loss of stroma (the serum), treat any possible infection (the ofloxacin), and keep the eye lubricated (the serum again & artificial tears [don’t give at the same time]).

Note that the author is doing the tear stimulant in the right eye but not the left (the ulcerated one). Technically we don’t want immunosuppression with a deep corneal ulcer if there’s infection present. For similar reasons the author won’t use a topical NSAID either (and we want vascularization to happen).

The owners should be prepped for what a perforation looks like - sudden increase in pain, watery discharge, the lack of a “divot” that turns into a plug of “mucous”, etc.

If by some small miracle the descemetocele epithelializes you will have a corneal “facet” but aren’t out of the woods yet. Instead of being one layer of tissue (Descemet’s membrane) away from a perforation you’ll have two layers (Descemet’s membrane and a layer of epithelium). Not ideal either. It will likely take months for stroma to build up between the two so ideally the dog would continue to wear the cone and be kept away from any traumatizing situations (dog parks, puppies, small toddlers, etc.). See more in Cornea.

# Surgical

In the dark days before optimmune, this was the most common treatment for KCS. Fortunately thanks to cyclosporine and its cousins (tacrolimus, etc.) it’s rare for this produre to be performed. This is typically a referral surgery as proper understanding of the anatomy is crucial for success but having an understanding of what to expect if this to be performed is good to communicate to owners.

In short, the parotid salivary duct is transposed to the conjunctival sac and the dog is trained to salivate in order to moisture the eye. In general the surgery is successful (meaning we succeed in bringing the duct up) but complications abound. Potential complications: overflow of moisture onto the face (a near certainty), corneal mineralization, fibrosis of the duct, poor salivary secretions, sialolith formation, general intolerance of saliva in the eye (i.e. persistent blepharospasm or pain or irritation).

Ultimately saliva is not a great substitute for tears as the concentration of “solids” in saliva is much higher.

The author has had only one good case (out of a small handful) where the dog was a lab that roamed around the farm and was much more comfortable but had a chronically wet face. He was out all the time and was not a lap dog and the owners therefore didn’t have to deal with it.

In the literature[2], the “success rate” is much higher although complications were noted to occur in 50% of dogs. The majority of owners indicated they would do it again - so maybe it’s not so bad. Still, many ophthalmologist consider this surgery one of last resort for unresponsive cases.

# Qualitative KCS

A differential diagnosis whenever chronic keratoconjunctivitis is noted in an animal but with normal STT. Usually these eyes have a kind of “lack luster” appearance that looks dry but when tested with a Schirmer’s is normal. Recall that the tear film has 3 components - aqueous, lipid, mucous. If the aqueous is fine (normal STT) you can still have issues with lipid and mucous. Affecting these components will not lead to lowered STT but can affect the stability of the tears. Both lipid and mucin help to maintain the surface of tears across the eye (otherwise it would just sink to the bottom of the eye with gravity). The surface tension is helped by these parts of the tear film.

Absence or deficiency of these components will lead to premature “breakup” of the tear film that causes similar signs as lack of the aqueous component.

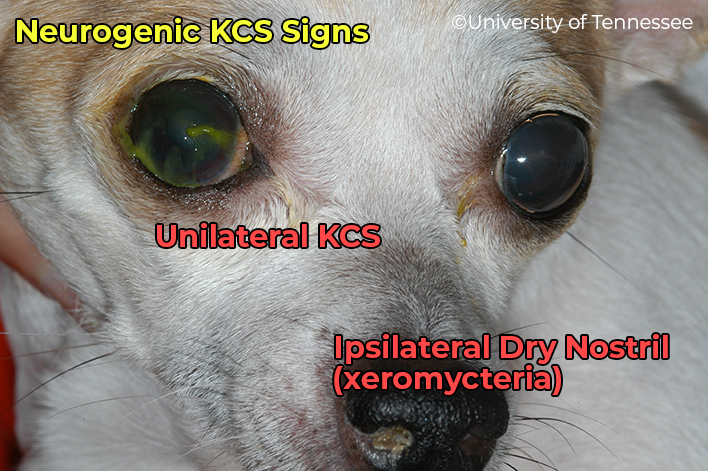

# Neurogenic KCS

A special mention should be made with a specific type of KCS - neurogenic KCS (#6 in the above list). Neurogenic KCS deserves a special mention because it doesn’t tend to act like “normal” immune-mediated KCS. The parasympathetic fiber pathway to the lacrimal gland is rather complicated and jumps around various nerves before making its way to the gland. With respect to neurogenic KCS, two facts with regards to parasympathetic innervation/nerve fibers should be kept in mind:

- The fibers travels through or near the middle ear.

- The fibers branch off to the nasal gland before reaching the lacrimal gland. Prior to the branching the innervation is common to both glands.

Fact #1 is important because it should be kept in mind that middle ear disease or otitis media can result in neurogenic KCS. If you have a dog with a history of ear infections (e.g. Cockers or labs that go swimming a lot) or if there’s a recent history of ear flushing or treatment, then otitis media should be on your differential list of possible underlying cause. It’s impossible to directly visualize the middle ear but an otoscopic exam can be attempted to at least visualize the ear drum and whether or not it’s intact. Failing that, a CT scan may be the best choice if a definitive assessment is needed.

Fact #2 is important because if the lesion affects the “common” pathway it will knock out both the nasal gland (which keeps the nostril moist) and the lacrimal gland. Usually these dogs will have a “plug” of gross dried mucous in their nose (see below).

Treatment for neurogenic KCS is hopefully directed at an underlying cause (e.g. hypothyroidism, middle ear disease) but absent any recognizable underlying problem (e.g. antibiotics for otitis, thyroid supplement for hypothyroidism), treatment can be geared toward increasing the parasympathetic tone to the lacrimal gland. The way to do so with is with a parasympathomimetic agent such as pilocarpine in addition to the usual KCS treatments described above this section.

TIP

Pilocarpine treatment is a bit weird for neurogenic KCS. The “rule of 2s” is something that someone somewhere made up and has no real definitive evidence for but is an informal guide to dosing with pilocarpine. The “rule” is:

Give 2 drops of 2% pilocarpine 2 times a day for every 20 lbs of dog.

The 2% pilocarpine is an topical ophthalmic drop that is placed in food (sometimes this will confuse the pharmacists who will call you.)

The above dose (e.g. 2 drops for a 20 lb dog BID) is just the starting dose. Owners should be instructed to increase the frquency of medications by 1 drop per day after a few days of the same dose and to monitor stools. If/when the stools become soft (starting to enter diarrhea territory) then decrease by a drop per day. The best way to explain the process is with an example.

EXAMPLE: With a 10lb dog the dose would be 1 drop AM & PM PO (in food). After 3-4 days, if no diarrhea noted, goes to 2 drops AM & 1 drop PM. After 3-4 days with no soft stools, increase to 2 drops AM & 2 drops PM. Oops, on day 2 soft stools are noted so dose goes back to 2 drops AM and 1 drop PM until recheck (usually within a month).

The rationale with doing this is that by dosing with a parasympathomimetic we hope to systemically increase parasympathetic tone which may affect the lacrimal gland but also cause increased gut motility (recall organophosphate toxicity that results in SLUD by inhibiting the action of acetylcholinesterase [thus indirectly increasing PS tone]. We want the Lacrimation but not the Diarrhea [and I guess we don’t really care about the S or U] so we try to push it as far as we can).

For a small retrospective describing neurogenic KCS see the below reference.[3]

References/Footnotes

An investigation comparing the efficacy of topical ocular application of tacrolimus and cyclosporine in dogs. Hendrix DV, Adkins EA, Ward DA, Stuffle J, Skorobohach B., Vet Med Int. 2011;2011:487592. doi: 10.4061/2011/487592. ↩︎

Parotid duct transposition in dogs: a retrospective review of 92 eyes from 1999 to 2009. Vet Ophthalmol . 2012 Jul;15(4):213-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2011.00972.x. ↩︎

Canine neurogenic Keratoconjunctivitis sicca: 11 cases (2006-2010). Matheis FL, Walser-Reinhardt L, Spiess BM. Vet Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul;15(4):288-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2011.00968.x. Epub 2011 Oct 31. PMID: 22051024 ↩︎