# Conjunctiva & Nictitans

The conjunctiva is the mucous membrane that surrounds the eye. It is the most exposed mucous membrane of the body. The conjunctiva passes over the nictitans (third eyelid) lining this part of the adnexa as well as the interior surface of the eyelid and anterior aspect of the globe.

The nictitans or third eyelid, is a conjunctival-lined structure found at the ventromedial aspect of the eye.

# Conjunctival Anatomy and Physiology

The conjunctiva is technically one continuous tissue but has 3 different “parts” that more or less reflect the surface that it lines. The 3 parts are:

- Palpebral conjunctiva - the part that is attached to the eyelids

- Bulbar conjunctiva - the part that lines the exterior aspect of the globe

- Conjunctival fornix - the “in between” part between the palpebral conjunctiva and the bulbar conjunctiva that forms a blind pouch posteriorly as the conjunctiva reflects onto the globe from the eyelid (or vice versa)

Histologically the conjunctiva is made of 2 layers

- Superficial: Non-keratinized epithelium with goblet cells - these produce the mucin layer of the tear film

- Deep: Substantia propria with lymphocyte and fibrous layers, aka “Tenon’s capsule”

TIP

The conjunctival epithelium can be pigmented - this is normal and is not a concern. If the pigment should ever cross over the limbus into the cornea then that’s abnormal. Sometimes people will note pigmentation within the conjunctiva and become alarmed that it is melanoma. If the pigmentation is flat and well-circumscribed then it most likely not a concern.

# Diseases of the Conjunctiva

# Inflammation - Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is a common diagnosis for “red eye” of nonspecific origin. It should be noted that a diagnosis of conjunctivitis should only be made after ensuring that ocular inflammation or other disease is not present anywhere else in the eye. Often times the conjunctiva will appear hyperemic in cases of glaucoma or uveitis, and treatment with topical antibiotics or weak anti-inflammatories will do little to address the primary problem. This is to say that signs of conjunctivitis such as hyperemia may not be specifically inflammation of this tissue but rather dilation of the vessels in response to other ocular morbities.

Clinical signs:

- Blepharospasm (mild-moderate)

- Conjunctival hyperemia (different than episcleral injection)

- +/- Chemosis

- +/- Ocular discharge - mucoid or otherwise

Note that these clinical signs are mostly similar for all of the below etiologies so it’s not like you can distinguish one from another based on how it looks i.e. you can’t tell something is allergic vs irritative based on the specifics of how the conjunctivitis appears.

Ultimately a diagnosis is made based on history (e.g. outside a lot, concurrent atopy, changing seasons), examination, signalment, and sometimes response to treatment. Below are a list of specific primary etiologies. These include:

- Follicular conjunctivitis

- Allergic conjunctivitis

- Viral conjunctivitis

- Physical/Environmental irritation (wind, dust, the elements)

# Follicular conjunctivitis

Probably the “easiest” conjunctivitis to diagnose. It’s typically characterized by conjunctival follicles noted on the bulbar & palpebral aspect or fornix associated with the third eyelid. The etiology is suspected to be from a hyperactive immune system that is learning to cope with the world of possible allergens (hence the young age of most affected animals).

Diagnosis:

- Signalment - usually occurs in YOUNG dogs

- History - presents with red eyes with mild-moderate ocular discharge, maybe some rubbing or squinting

- Exam - conjunctival hyperemia but with follicles noted on the conjunctival surface - usually most severe in the fornix associated with the third eyelid

- These are typical-looking follicles in a young dog with follicular conjunctivitis.

- The follicles can be hard to see without good light and magnifications - so use your equipment!

- Remember to lower the eyelid and elevate the third eyelid by retropulsion to get the best visualization of them.

- Once noted on the palpebral surface, you can check the posterior surface too but the diagnosis is clear. Sometimes, you can have more posteriorly vs anteriorly or vice versa so it's nice to check both surfaces to be thorough.

Treatment:

- Follicular conjunctivitis is largely self-limiting and gradually recedes as the animal gets older

- To improve clinical signs, the author will usually prescribe NeoPolyDex ointment or drops BID for 2 weeks past clinical resolution (usually 3-4 weeks total)

- In cases where clinical signs recur after discontinuing the medication, the follicles can be debrided to convert a “chronic conjunctivitis” to a more “acute conjunctivitis” which may be more responsive to the topical steroids

- Debridement is essentially done with a scalpel blade scraped against the follicles to rupture them (sedation & topical anesthetics is advised)

- Regular flushing of the eyes may also help reduce antigen load

TIP

To examine the palpebral aspect of the third eyelid, you can use one hand to hold the transilluminator while the other hand opens up the eye (usually the author will use the index finger for the upper lid and his thumb for the lower). While the lids are open, press gently through the upper lid onto the globe to retropulse it which will cause the third eyelid to elevate. With the finger on the lower lid, lower the lower eyelid to better visualize the fornix for follicles (or debris or whatever).

To examine the bulbar aspect of the third eyelid is a little trickier but sorta easy. Apply a drop of proparacaine, wait 30-60 seconds for it to have an effect, open the lids with a speculum (ideally to free up a hand) and then while holding a light, use a q-tip to go under the third eyelid and bring it out rostrally while peeking over it (like looking into a pocket from the top).

# Allergic conjunctivitis

- Just like people, dogs can get allergic conjunctivitis. There’s no way to know for sure if a conjunctivitis is secondary to allergies although having concurrent atopy or signs of atopy (e.g. paw licking, pyoderma, etc.) is helpful in lending weight to the diagnosis.

Diagnosis:

- Does the dog live in a hermetic bubble? No? The environment could be responsible.

- Any history of being outside and exposed to air containing allergens or particulate matter? Yes? The environment could be responsible.

- Any history of allergies to other things? Atopy? Yes? Maybe it’s allergies!

- You get the idea - make sure you do a full ophthalmic exam including a STT, stain, and IOP before coming to a diagnosis of conjunctivitis for a patient

Treatment:

- If the animal does have active signs of atopy, treatment for the atopy (atopica, steroids, fancy antibody injections) may also help with the conjunctivitis so don’t ignore or avoid the larger conversation about allergies

- Usually treatment proceeds in the absence of a firm diagnosis (and a complete ophthalmic exam including a STT, IOP, and stain)

- The author will usually progress in the following fashion with medications:

- Topical anti-histamines - usually hit or miss when it comes to dogs, sometimes works great, sometimes not at all. There are a plethora of different human ones but usually the author will do Zaditor (brandname)/Ketotifen (generic) BID-TID

- Topical NSAID - reportedly there is some anti-histamine capability for some topical NSAID, in particular ketorolac BID-TID

- Topical cyclosporine/optimmune - no real evidence in treatment of allergies but more tears may mean less residence-time of allergens on the corneal surface and there’s also an “anti-inflammatory” or immune-modulatory effect as well. May cause epiphora though so the author will usually use no more than q12-24h. Many “allergic” dogs may also have immune-mediated keratitis that could be covered by this and steroids (see below)

- Topical steroids - the “nuclear” option for allergies is topical steroids (e.g. dexamethasone or NPD or NPB-HC). It’s rare to have to go this far but if signs are severe or persistent enough can try. If the redness does not respond to anything but steroids the diagnosis should be reconsidered - it still could be conjunctivitis but perhaps more immune-mediated vs excessive response to environmental allergens

- Treatment usually goes for about 2 weeks (or past the time of allergy season) past clinical resolution

- Note on antibiotics - technically the problem is not primarily bacterial (primary bacterial conjunctivitis is rare) so prescribing something like gentamicin or tobramycin for allergic conjunctivitis doesn’t make much sense; there could be bacterial overgrowth with alteration of the normal physiology but it’s not technically an “infection” in the same way as a pyoderma. NeoPolyDex is generally less expensive than straight up dexamethasone so the author will use NPD even though the “NP” part may not be medically necessarily.

# Viral conjunctivitis

- Relatively uncommon etiology of conjunctivitis in dogs - main two culprits are distemper virus (CDV) and canine herpes virus (CHV-1)

- Canine Distemper Virus (CDV)

- Results in conjunctivitis, KCS, neurological changes, other systemic effects

- Can present with thick mucoid discharge from conjunctivitis and KCS along with upper respiratory signs (e.g. rhinitis)

- Diagnosti:

- Ideally antigen tests for CDV: IFA or PCR

- Could do conjunctival cytology to look for inclusion bodies but pretty rare to actually find

- Treatment:

- Topical antibiotics for secondary infection

- Topical lubricants if KCS is also present

- Supportive care

- Canine Herpes Virus (CHV)

- Relatively new (early 2000s) entrant onto the canine conjunctivitis scene

- Can result in ulcerative/non-ulcerative keratitis

- Actual prevalence among the general population of dogs is probably small (in contrast to the feline version) but difficult to say without bigger studies

- Sexually intact dogs with frequent exposure to other dogs may increase risk

- Diagnosis:

- History of being exposed to a lot of dogs

- Antibody testing (blood) or PCR (swabs)

- Treatment:

- Usually self-limiting (resolves in a few weeks) but can do topical anti-virals (the usual ones, similar to what’s used in cats)

- Idoxuridine & Trifluridine q6-8h has been reported (will need to be compounded)

# Physical/Environmental irritation

- In this large and nebulous category is conjunctivitis from drugs (topical), wind, dust, and eyelid disease such as entropion and ectropion

- Of these, entropion is probably the most problematic because this is a problem that will need to be addressed - usually there’s also concurrent keratitis at the same time

- The exception is for some breeds that have a “natural” medial entropion - bulldogs & pugs usually

- These dogs most likely have had the issue with “entropion” life-long to some degree and it’d be weird to suddenly develop a random problem with it in the form of overt acute conjunctivitis

Diagnosis:

- Similar to allergic conjunctivitis - any history of exposure to the “environment”? Could be the wind, dust, pollen, random leaf of a bush that the eye brushed up against, etc. Dogs can do some pretty bizarre things:

Maybe this dog is going to have a weird conjunctivitis OD?

Diagnosis (continued):

- Good history including any signs of atopy or weird exposure

- Complete ophthalmic exam to rule out any other factors including entropion/ectropion - do the eyelid margins make good normal contact with the cornea?

Treatment:

- If eyelid problem → fix it (see Eyelid for more information on specific problems)

- Most physical irritants are self-limiting but generally treatment protocol follows the rulebook for Allergic Conjunctivitis treatment

# Brief comment on Bacterial conjunctivitis

Primary bacterial conjunctivitis isn’t really a thing - usually bacterial overgrowth is secondary to KCS which should be treated. So don’t just go through all the topical antibiotics (or systemic) because you’ll eventually create a monster population of resistent bacteria on the conjunctival surface.

If you really don’t have any other predisposing disease then can determine population of bacteria and treat according to results of culture.

# Hemorrhage

Conjunctival hemorrhage is usually thought of as a manifestation of systemic disease including coagulopathies (petechia, ecchymoses, etc.) or trauma (hemorrhage throughout).

Etiologies:

- Trauma, tick borne disease, choke collars, certain neurologic events, blood dyscrasias etc.

Diagnostics:

- History, physical examination, CBC, panel, coag, etc. when indicated.

Treatment:

- Address primary disease if diagnosed

- No treatment necessary if it is secondary to trauma if the rest of the eye is normal but if the eye is affected (uveitis) treat accordingly (anti-inflammatories).

# Neoplasia

Conjunctival neoplasia is uncommon but can occur. Reported types include:

- Papilloma

- Hemangioma/Hemangiosarcoma

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Epithelioma

- Melanoma

- Mast cell tumors

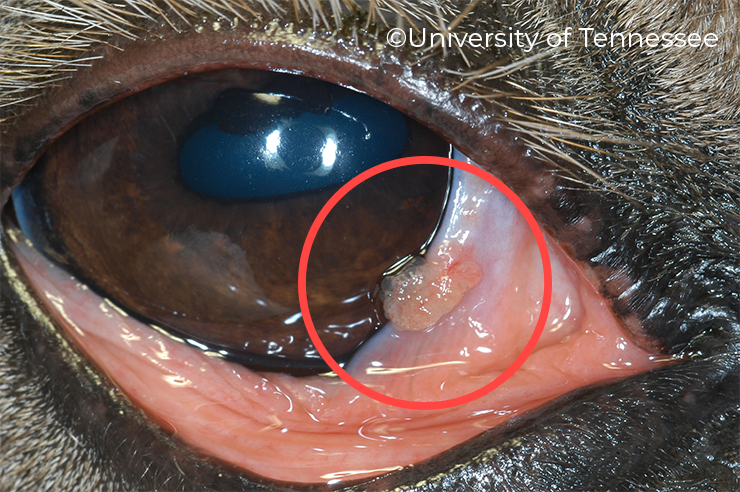

- Typical appearance of a conjunctival papilloma

- If you were to examine the base, may be on a stalk (like a piece of broccoli or cauliflower)

- Another differential would be SCC (big difference so remember to biopsy and submit to your friendly neighborhood pathologist)

Diagnostics:

- Biopsy!

- The conjunctiva is an incredibly easy tissue to biopsy - the mass can be lifted up with small forceps and resected usually with small scissors (e.g. iris or tenotomy)

- Afterwards, no sutures are needed to close as usually second-intention healing occurs within days

- Bleeding is normal and typically stops after a minute or two (no animal is going to bleed out from nicking some conjunctival vessels unless there’s a SERIOUS problem)

- If the mass is “deeper” and you can’t just pick it up, then a small skin punch is typically needed to “core out” a portion of the mass for histo

- Usually the author will approach it from the conjunctival side - no need to stitch anything! vs the skin

- Cytology? - not really worth it, might just get superficial epithelial cells that are not going to be very diagnostic

Treatment:

- Depends on specific type of tumor - e.g. snip and freeze for papilloma or hemangioma, more radical resection with SCC or more aggressive neoplasias

WARNING

Some conjunctival tumors can metastasize to else where in the body at potentially greater rates than eyelid tumors so they are not quite the same. Staging can be performed when biopsies return as more malignant-looking tumors.

# Nictitans Anatomy & Physiology

Important facts:

- Conjunctiva: lines both sides of the third eyelid

- Cartilage: T-shaped with the base towards the medial fornix and the top along the leading edge. This cartilage stops the nictitans from buckling

- A lacrimal gland is present on the bulbar side of the nictitans

# Functions

- Protection of the cornea

- Production of 35% of the aqueous part of the tear film

- Reticuloendothelial activity

# How to look at it!

- Retropulse the globe which will cause the third eyelid to elevate upwards

- Take a pair of non-traumatic forces and lift up and out

- Take a cotton-tipped applicator and roll it under the third eyelid and lift outward (author’s favorite)

# Diseases of the Nictitans

# Prolapse of the Gland/Cherry eye

Probably THE most common third eyelid primary complaint encountered in veterinary medicine. Prolapse of the gland of the nictitans towards or over the leading edge of the nictitans. It is suspected that the ligamentous structure that normally holds the gland in place is weak. Cocker Spaniels and English bulldogs are predisposed but the condition can occur in any breed.

- Note the smooth margin (vs the tumor below which is more irregular)

- The third eyelid cartilage is underneath or ventral to the cherry eye

- When you see these in a giant breed dog, check for a scrolled cartilage by lifting up the gland to visualize the cartilage (see the "Scrolled Cartilage" section below)

# Treatment:

Medical/Non-surgical

- Manual replacement - described in any number of YouTube videos, stuffing the cherry eye back in can work temporarily but as the gland swells from repeated reproplapsing and exposure, this becomes less and less likely to work (if it even does anything longterm)

- Topical steroids - in the author’s experience, topical or oral anti-inflammatories do practically nothing to reduce the size of the gland once prolapsed or help with the resultant local conjunctivitis but if you want to try, then can do NPD ointment or drop BID-TID

Surgical

- Replacement surgical treatment is the recommended treatment for cherry eye in order to increase the chance of preserving function. Recall that the gland of the third eyelid is estimated to provide at least a third of the tear production

A nice review of all the different kinds of techniques and their success rates can be found here (opens new window)[1].

The two most commonly used ways to treat this are:

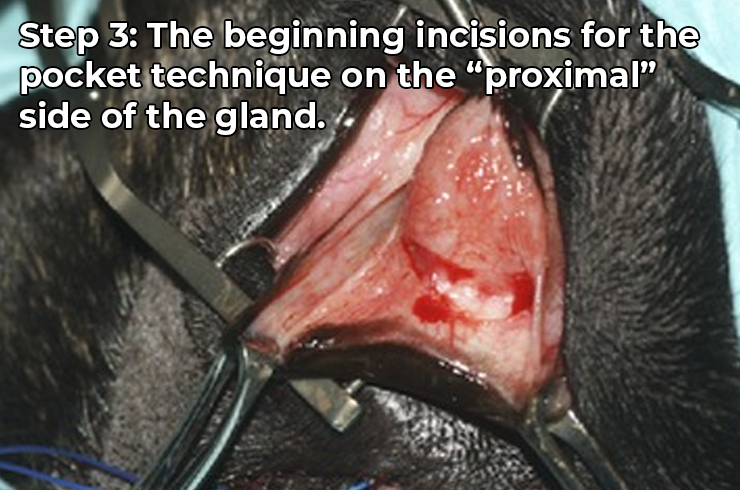

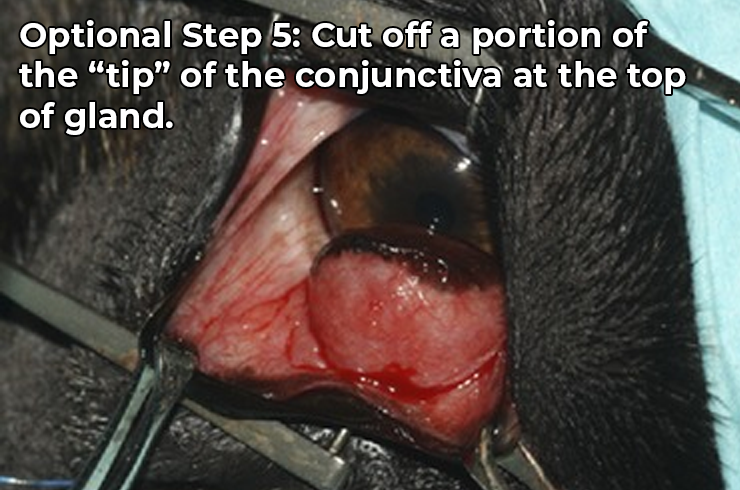

- Pocket Technique:

Usually a little easier to do then the tack, the pocket (most popular is the modified Morgan Pocket) is author’s preferred method of treating prolapsed glands. Below is a good video illustrating the technique by ophthalmologist, Ken Abrams DACVO.

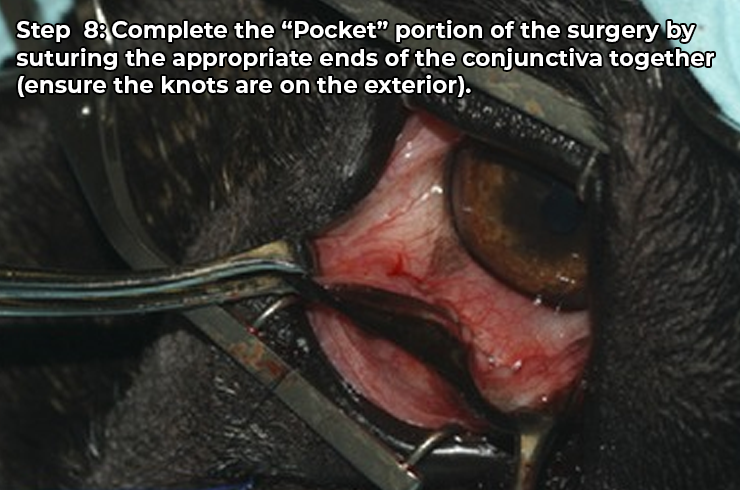

It’s important to get proper apposition of the distal edge of the distal incision of the conjunctiva with the promxial edge of the proximal incision. If you understand the previous sentence, chances are you understand how the pocket technique works!

The main variations (the “modifiers”) with the pocket are usually how the incision is secured after the first row of simple continuous sutures are placed. This could include double-backing with an inverting suture pattern (Cushing/Connell) or the “full thickness” semi-mattress pattern in the above video. Ultimately the goal is to try to keep the edges of conjunctiva together long enough to scar together and also to prevent any rubbing of suture against the cornea resulting in a corneal ulcer.

Remember to use a soft smaller suture (please don’t use 3-0 PDS) as there’ll be less chance of having a serious ulcer with a small multifilament suture. The author usually prefers 5-0 or 6-0 Vicryl.

Reported failures rates for the Morgan technique (and all its variants) ranged from 0-12.5% (so at least a 90% success rate to put a positive spin on it). Breed-associated failures have not been definitively proven but amongst ophthalmologists anecdotally there’s a lot of hand wringing and head shaking associated with English Bulldogs, giant breed dogs, and at the time of writing, the new hot(mess of a breed) French bulldog.

- Tackdown method(s):

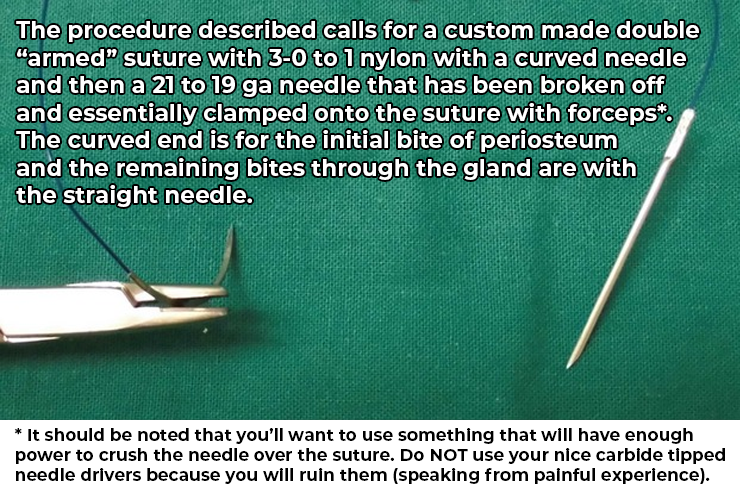

Slightly more complicated because the anatomy involved in tackdowns is more complicated. In brachycephalics, the ventral orbit may be awkwardly posterior to the globe making placement of the suture more awkward. There have been some variations of the ventral orbit tackdown.

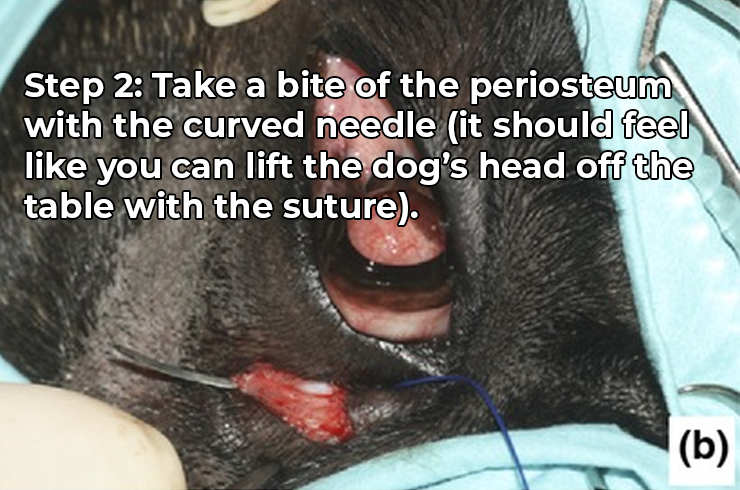

Tackdowns are genrally more difficult when first learning. The suture pattern for some needs to be done in order to be fully understand in the author’s humble opinion. There are usually a few places the gland can be tacked. The most common is tacking it to the periosteum of the orbital rim near/ventral to the gland but it can also be tacked to the T-cartilage and the ventral rectus muscle of the eye. See below for descriptions of each.

Ventral orbit periosteal tackdown - there are several variations of the periosteal tackdown, but a good version that the author likes is described actually in the “combination” paper described below (excluding the pocket stuff). One thing to warn owners is that bringing the gland ventrally to the orbit tends to see-saw the third eyelid up/dorsally so it’ll be more obvious (like a Horner’s eye almost but without the enophthalmia).

Third eyelid cartilage tackdown - per personal communication with the author: good for small glands. Read the paper here for description of the technique. (opens new window)[2]. Essentially the gland is tacked to the base of the cartilage (the vertical part of the “T”):

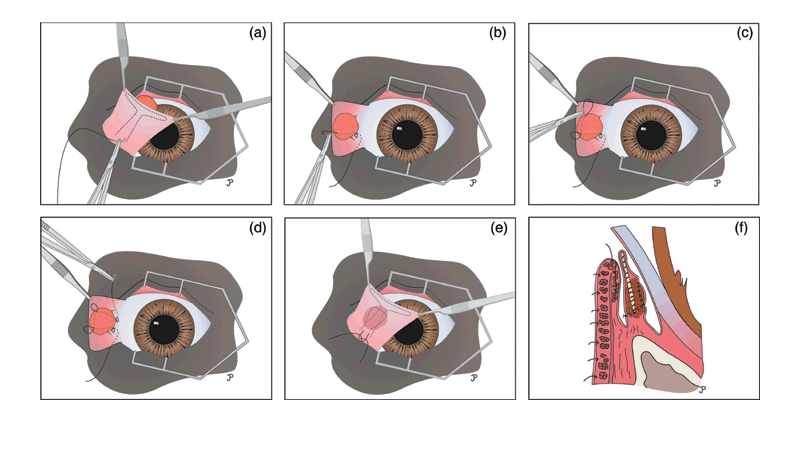

Intranictitans tacking (Fig 1 from Plummer et al paper) - Diagram showing how the suture is placed (similar pattern to orbital tacking) to keep suture buried under conjunctiva of gland (so doesn't abrade cornea)

- Ventral Rectus Muscle tackdown - probably one of the more exotic techniques. Probably not recommended for a general practitioner due to the complexity of trying to wrap the gland to the ventral rectus muscle; missing it will probably mean wrapping it around connective tissue with higher chance of failure. The paper describing the technique is here (opens new window)[3] and there’s also a video illustrating it (opens new window)(not embedded here because of age restrictions[hopefully you’re old enough to watch it])

- Combination:

The “belt and suspenders” approach to trying to correct cherry eyes. The technique is generally to combine the pocket technique with the periosteal tackdown as described in this paper (opens new window)[4]. The question inevitably asked is What comes first? and the answer is the tackdown first (although the incisions for the pocket usually precede it).

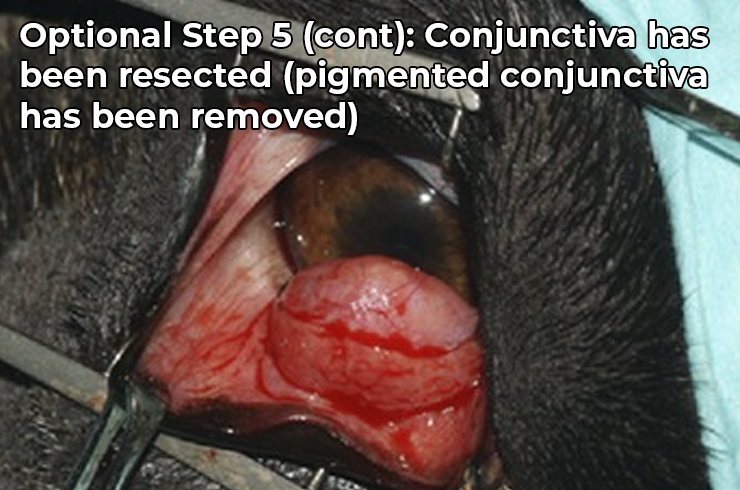

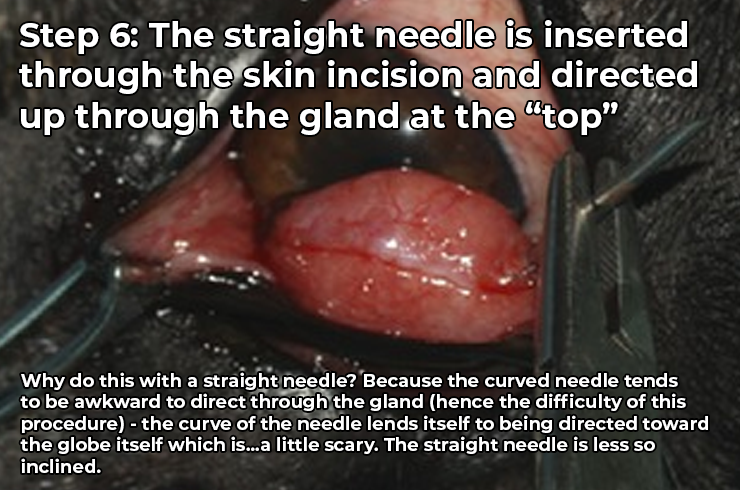

In the paper, the authors report a better rate of success for challenging breeds (e.g. English Bulldog) and an overall success rate of 95%. Below is a slide show from the paper that illustrates the combo procedure (which is also handy for understanding both the tacking and pocket techniques separately).

# Neoplasia of the Gland

- Rare, but usually presents as exophthalmia or globe deviation (see: Orbital Neoplasia)

- Can be adenoma or adenocarcinoma

- This tumor has extended up and out of the orbit

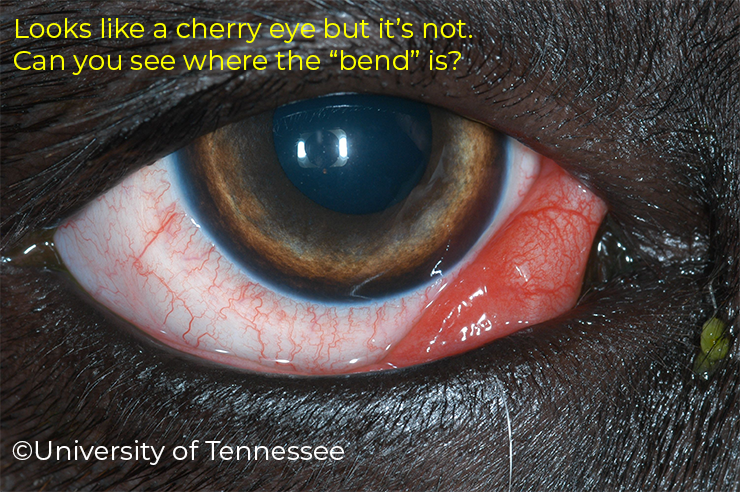

- How do you know this isn't a cherry eye? It's not a cherry eye because you can still see the margin of the third eyelid. A prolapsed gland typically extrudes out and over the margin of the third eyelid (see above section on prolapsed gland of the nictitans)

- The author would likely recommend incisional or excisional biopsy either by doing a skin punch (for incisional) or excising as much of the third eyelid as possible with the mass (for attempted excisional) depending on whether or not it seemed feasible while the dog was under general anesthesia

- Enucleation could be considered but is rare in the author's limited experience

# Scrolled/Everted/Bent cartilage

- Typically occurs in giant breed dogs

- Can be confused for prolapse of the gland of the third eyelid

- Essentially this is an abnormal bend in the vertical part of the cartilage that causes the horizontal part of the T to bend forward (almost like it’s doing a “forward fold” yoga pose)

- Treatment:

- Usually cutting over the “bend” and blunt dissection of the overlying conjunctiva (can be tight so use blunt tipped small scissors)

- Once the cartilage is isolated away from the conjunctiva, the “bend” is cut out as one piece (feels a little weird but hey it works)

- This may result in the third eyelid naturally returning to its normal conformation or if the bend is still in place, additional suturing of the conjunctiva (usually with 6-0 Vicyrl or smaller) to “tighten” the conjunctiva posteriorly may be needed to return the third eyelid to a normal position - similar to what you would do with a Morgan Pocket

- Another cooler newer technique is the use of cautery/heat to essential mold the bend away by softening the cartilage with heat

WARNING

Prolapse of gland of the third eyelid can occur during or shortly after correction. Owners may see “recurrence” but unfortunately it may be because the gland has prolapsed out recreating the pink-thing-in-the-corner of the eye again. Because of this and the chance of the third eyelid to remain bent after transection, usually the author recommends these cases be referred.

# Trauma

Laceration to the third eyelid may cause significant swelling or chemosis of the third eyelid. In most cases, attention should be directed to the globe to make sure it is unharmed. Any damage to the eye itself should take precedence. Often times if it’s just the third eyelid that is affected, the author will recommend systemic treatment with NSAIDs and topical antibiotics. Whatever swelling and inflammation of the third eyelid usually subsides within a couple weeks and any wounds allowed to heal by second intention - large lacerations can contract to a significant degree. If there’s a piece that is literally hanging by a thread, then for neatness sake, it can be trimmed off, but this is rare.

- Partial third eyelid laceration with corneal ulcer too laterally

- The eye is mostly intact and presumably the third eyelid protected the eye from the brunt of the trauma like it's supposed to

References/Footnotes

An Evidence-Based Rapid Review of Surgical Techniques for Correction of Prolapsed Nictitans Glands in Dogs. Vet Sci. 2018 Aug 23;5(3):75. doi: 10.3390/vetsci5030075. ↩︎

Intranictitans tacking for replacement of prolapsed gland of the third eyelid in dogs, Vet Ophthalmol . Jul-Aug 2008;11(4):228-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2008.00630.x. ↩︎

Suture anchor placement technique around the insertion of the ventral rectus muscle for the replacement of the prolapsed gland of the third eyelid in dogs: 100 dogs, Vet Ophthalmol . 2014 Mar;17(2):81-6. doi: 10.1111/vop.12073. Epub 2013 Jul 24 ↩︎

Pocket technique or pocket technique combined with modified orbital rim anchorage for the replacement of a prolapsed gland of the third eyelid in dogs: 353 dogs, Vet Ophthalmol. 2016 May;19(3):214-9. doi: 10.1111/vop.12286. Epub 2015 Jun 10 ↩︎

← KCS/Dry Eye Cornea →